What on Earth is the Doughnut?…

June 6, 2022

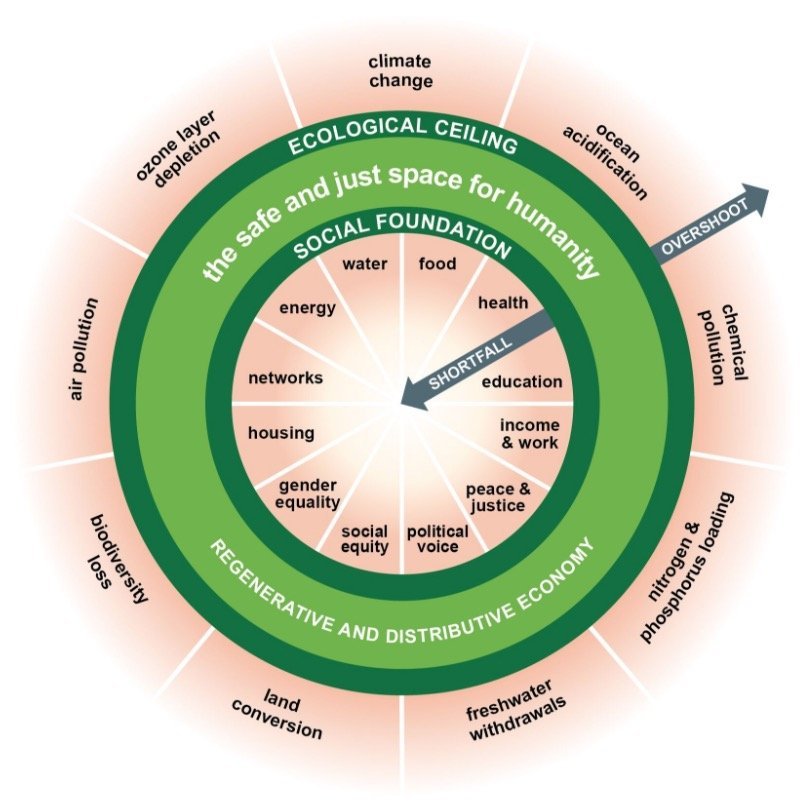

Recently I’ve been reading Kate Raworth’s book ‘Doughnut Economics’ and reflecting on our role as architects within the circular economy. From our inception as a practice we have considered how our projects can minimise their environmental footprint, and during my training, William McDonough’s book ‘Cradle to Cradle’ ignited a passion for these principles within me from a design perspective. Doughnut Economics goes further, framing how the entire economic ecosystem has to shift and function so that we operate with the safe limits of the planet. The doughnut diagram is an elegant representation of the principles, and inspired our own ethical compass developed recently to guide our work as a practice.

From her website, Raworth says:

“Humanity’s 21st century challenge is to meet the needs of all within the means of the planet. In other words, to ensure that no one falls short on life’s essentials (from food and housing to healthcare and political voice), while ensuring that collectively we do not overshoot our pressure on Earth’s life-supporting systems, on which we fundamentally depend – such as a stable climate, fertile soils, and a protective ozone layer. The Doughnut of social and planetary boundaries is a playfully serious approach to framing that challenge, and it acts as a compass for human progress this century.”

As architects and designers, we’re passionate about operating within our own sphere of influence, and this means looking seriously at the following design and specification issues as key to building within a circular economy:

‘Design for disassembly’ - enabling buildings to come apart well, so that components can be reused, or safely returned into the earth without harm at the end of their useful life;

‘Ecological Materials’ - specifying and using materials which are natural, biodegradable, have limited processing, and do not contain substances or chemicals which are harmful to life;

‘Design out Waste’ - at the design stage, we can have a big influence on how efficiently materials can be used. We seek to minimise waste through modular design, based on the use of whole standard materials;

‘Buildings that Learn’ - we recognise that buildings evolve, change, adapt and develop over time to suit users needs. We consider how services, finishes, and the ‘loose fit’ parts of a building can be easily replaced to avoid the need to rebuild;

‘Make it Durable’ - robust, durable, and adaptable buildings are likely to last longer and therefore spread their embodied carbon over a longer period of time. We weigh up the value of permanence and durability for higher embodied carbon components (superstructure);

‘Build with Carbon’ - ‘embodied energy’ is the amount of energy (and carbon) required to make materials used in a building. We strive to use low embodied energy materials such as earth, timber, straw and hemp (which sequester carbon in production), wherever technically viable;

‘Retrofit First’ - many buildings are being bulldozed in favour of retrofitting and repurposing. We favour a retrofit first approach that seeks to reuse the high embodied carbon superstructure components (foundations, walls, floors, roofs) wherever possible.

12 years ago to the day, Sam started making the rammed chalk walls to his parents’ house in Dorset, using site excavated earth (chalk) to form load bearing walls within timber formwork. The formwork (shuttering) of untreated timber and plywood was stripped clean, and then reused whole to form the first floor, walls, and roof to the building. Setting out the pre-fabricated glulam beam structure on a 2.4m grid minimised site waste, and allowed the use of whole sheets to mitigate cutting.